With the 11th century conversion to Christianity also came 37 saints’ days. On these days, ecclesiastical law stipulated that people were to lay down their work and attend Mass. It was the priests duty to notify his parishioners of the holy days. But the population was so scattered the priest could hardly be expected to reach all of them for every feast day. And so the “weather stick” became the “mass staff,” also known as rune stick or clog almanac. Failure to attend mass would result in a stiff fine. The Primstav helped Norwegians keep track of these saints’ days. It thus enabled them to observe their new religious commitments and avoid fines.

The Church brought with it the Julian Calendar, a chronology of months and days which was broken up by saints’ days and other holidays, some fixed and some (like Easter) movable. New sections were introduced into the laws of the land providing strict regulations for the observance of these days. No one must work on mass days, on penalty of heavy fines, for they were equally sacred with Sunday. Some of them were introduced by wakes and fasts on the preceding evening, while some were not. On some one could work till midday, while others were observed only by the avoidance of meat. It was not easy for the newly converted Christian to remember all this. So the law provided at the priests should send forth wooden crosses before each holy day to remind the people that it was coming. In later tradition, according to Olav Riste, those who had calendar sticks and could read them were under obligation to take them along to church and tell the others how many days were left until the next holy day and what activities were permissible and appropriate in the meantime.

The 4 greatest church feast days were Christmas, Mary’s Spring Festival, Midsummer’s Day and Michaelmas.

In 1537 came the Lutheran Reformation: The veneration of saints was outlawed. The Norwegian people began to give alternative meanings to the Primstav symbols. They reinterpreted the saints’ attributes to make them more relevant to their own daily lives. pagan symbols remained, not only because they were so much a part of the ancient culture, but also the church had retained some of the pagan celebrations and had given them religious significance.

Examples

July 29th. St. Olav was killed by an axe in the battle of Stiklestad in the year 1030. After the Reformation, St. Olav’s axe symbol reminded them that it was time to cut grass ad make hay.

August 24 is the day of Bartholomew, the apostle who was crucified and then flayed. The knife marking St. Bartholomew’s day signaled the start of the fall slaughter.

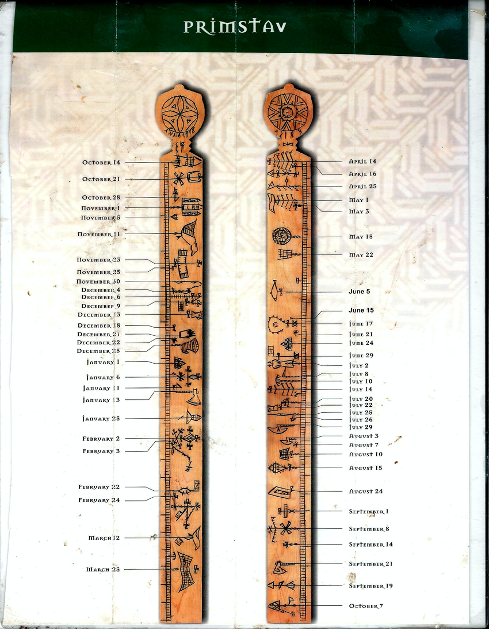

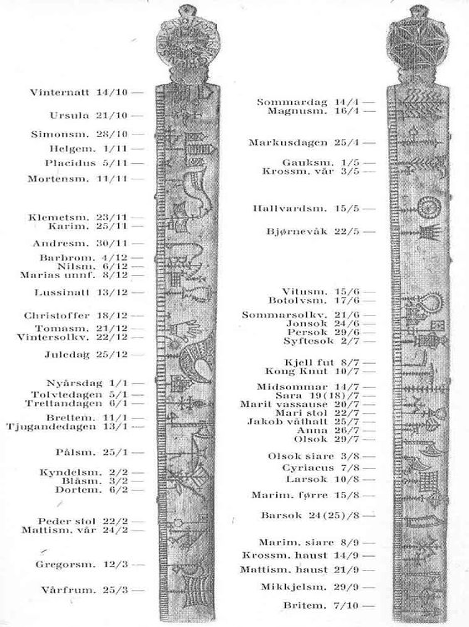

Symbols are used to mark saint’s days, holidays, nature/farming dates like planting harvest, butchering, good fishing and hunting times as well as tribal meeting dates. In folk tradition, the saint’ days came to be associated with nature and farming dates. Which merkedager were marked and which traditions were followed varied from place to place causing differences between calendars in marking holidays both in the choice of the days regarded as worth indicating and in the way of denoting them. Since farming conditions varied from north to south and east to the coastal west, the symbols on the primstav used differ widely.

Besides indicating seasonal tasks, some of the primstav’s merkedager reminded people to take special note of the weather on particular days for its clues to up-coming meteorological conditions. This information was vital to the pre-industrial Norwegian farmers, foresters, and fishermen, whose livelihoods depended on the weather in a time before the sophisticated forecasting we now take for granted. Given the short growing season, it was important to know the best time for seeding in the spring, or the time when the cattle might safely be let out to graze on the early pasture.

The majority of events correspond to local experience. None of the rules allow for individual opinions; it is collective opinions which are generally accepted, in the local society that people have lived in. They give the “right time” for seasons and all types of work, tell us whether we can expect a good or a bad harvest and tell us what sort of weather we have to expect. Some feast days intervene to regulate relations between neighbors, and for example, la down times for when gates should be open or shut, when animals should be received or handed back, and when cattle should be moved to or from the mountain pastures. Other feast days were “moving” days for servants, and others were semi-holy days when it was forbidden to work. And so the primstav is a meld of devotion to the saints (albeit tinged with some misinterpretation) and homage to weather and crop lore that went back to pagan times.

When the farmer talks about time, he hardly ever mentions the months; he refers everything to the season and the work connected with it. If he talks about events in the past, they occurred on Spring Day or at Peat Cutting Time, or in the Hay Harvest. If he is to be more precise, he clings as in the Catholic period to the best known saints’ days. This kind of reckoning has been called by some scholars an “economic” year, in contrast to the “astronomical” year.

Perhaps more than anything, the calendar stick gives us insight into how important tradition and customs were to these people who lived so closely with one another but so isolated from the rest of the world. If St. Simon’s Day was the day the cattle were moved indoors, it’s likely ALL the cattle in the parish found themselves indoors. An if St. Vitus’ Day was the day for cleaning the chimneys in the sheds used for smoking meats, it’s a safe bet the soot was flying throughout the whole valley. And woe to the careless soul who ventured out on the ice after St. Peter’s Day – if the ice gave way it was no one’s fault but his own!

The symbols on the Primstav varied according to climate and latitude. The customs of each locality had attached themselves to specific days to such an extent that many of the days were still in common use down into the literate era of the late nineteenth century. They were even listed in the official printed calendars until after the turn of the present century. Just as our Ground Hog Day (the old Candlemas) and Hallowe’en (the eve before All Saints’) carry on long after their original sense has been forgotten, so Michaelmas and Olaf’s Wake are living concepts to this day in the life of the Norwegian farmer.

The oldest calendar stick still in existence was made in 1457. One of the best preserved mass staff was carved in 1707 by Dreng BiØnso. It is known as the Valle stick, a name likely coming from Valle in Setesdalen. The original is in the Norwegian Folkemuseum in Oslo. The Primstav dates below refer to the Valle stick. The oldest surviving Primstav dates from about 1200 AD after the Christianization of Scandinavia and post